All’s Well That Ends Well Shakespeare Santa Cruz, 2008

Lisa Jensen – Good Times Santa Cruz

Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well is an odd romantic comedy. The lovers are not well-suited, and the nominal hero behaves very badly. In this tale of a woman attempting to trick a man who does not love her into happiness, even the title is intended ironically, as the audience ponders whether romantic ends justify dubious means.

In style and philosophy, it’s the opposite of Romeo and Juliet, which may be why Shakespeare Santa Cruz chose to stage both plays together in repertory this season. (They share the same functional Erhard Rom set of stone arches and catwalks.) While Romeo and Juliet, in feverish youth, are ready to die for love, the characters in All’s Well (written 10 years later) are challenged to live with compromise. To make the play palatable for modern audiences, director Tim Ocel plays up its comic strengths—including one of Shakespeare’s most entertaining rascals—while acknowledging its complexities in an often pensive production enlivened by wit and warmth.

Bertram (Erik Hellman), a young count on his way to court, leaves behind a household in mourning for his late father, including his widowed mother (the capable Beth Dixon) and her ward, Helena (Rachel Fowler). The daughter of the physician (now also deceased) who attended Bertram's father, Helena harbors an unrequited love for Bertram, who is far above her in station, although she's superior to the callow young count in wisdom and character.

At court, the King of France (the excellent and commanding Paul Vincent O’Connor) is dying of a rare disease. Helena arrives to cure him with her father's medicines, in exchange for the king’s support in selecting one of his courtiers for her husband. Of course, she chooses Bertram, who doesn't love her but dares not refuse an order from his newly invigorated king. Egged on by his friend, the cowardly braggart, Parolles (Allen Gilmore), Bertram flees to join the king’s army in Florence on his wedding night, rather than bed his new bride. Aghast that she’s driven her husband into war, Helena follows him to Florence. In cahoots with Diana (a vibrant Caitlin FitzGerald), with whom faithless Bertram has planned a tryst, she hatches a trick to consummate their marriage and bring her reluctant husband home.

Gilmore’s splendid Parolles is the tent-pole of this production—almost literally, in the gaudy ribbons and rags that festoon his cocky leather outfit, a bright visual respite from the somber mourning and military dress of B. Modern’s costume design in the play’s first half. Parolles is a rogue and troublemaker wise to his own failings, and Gilmore gives the production swaggering energy and heart. A master of quick-witted banter (he’s a riot debating the merits of virginity with Helena), Gilmore’s frisky irreverence can drop in a heartbeat to the most disarming and genuine pathos.

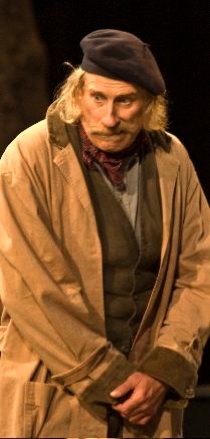

His fellow Bach At Leipzig co-stars Stephen Caffrey and Larry Paulsen, as courtier/soldiers the Dumaine brothers, are clear and witty in their sly observations. Saundra McClain plays Diana’s mother with tart, earthy warmth, and John Pribyl is a crowd-pleaser as the stumbling country clown and antic philosopher, Lavatch.

As Bertram, Hellman works hard in one of Shakespeare’s most thankless roles, delivering all the boyish petulance the part calls for, treading a fine line between outright meanness and honest outrage: it’s not his fault he’s coerced into a marriage he doesn’t want. (Although his behavior in Florence is less morally defensible; when Diana upbraids him for valuing the honor of his family ring above her virtue, she gets a round of applause.)

Fowler brings perhaps too much gravity to the already broody and reflective role of Helena. She never seems to get much joy from her illicit crush on Bertram (not that he gives her much cause), although Fowler perks up in her sparkling repartee with Parolles, and the playful way she teases, then reprieves the king’s other courtiers on her way to choosing her husband. But the uneasiness between these mismatched lovers is what the play is all about—which Ocel respects in a provocative coda where the couple end up not in a clinch, but sitting a little apart onstage, like the end of The Graduate, wondering what happens next.

Back to All’s Well That Ends Well Press...Back to Regional Theatre Resume...

John Prybl

All’s Well That Ends Well

Shakespeare

Shakespeare Santa Cruz

2008

Photo: r.r. jones